Taken from a talk and commission in 2021 to mark forty years since the publication of Lanark.

I started working for Alasdair in 2010. He’d been commissioned to make a mural for the Hillhead Subway station and I was asked to help. He said this mural wouldn’t take long to finish so I thought I’d be working for him for about a week. We worked on it every day for well over a year, and for the next few years we worked on lots of other paintings and illustrations, some of them new, some of them he’d started in the 50s, and others in between.

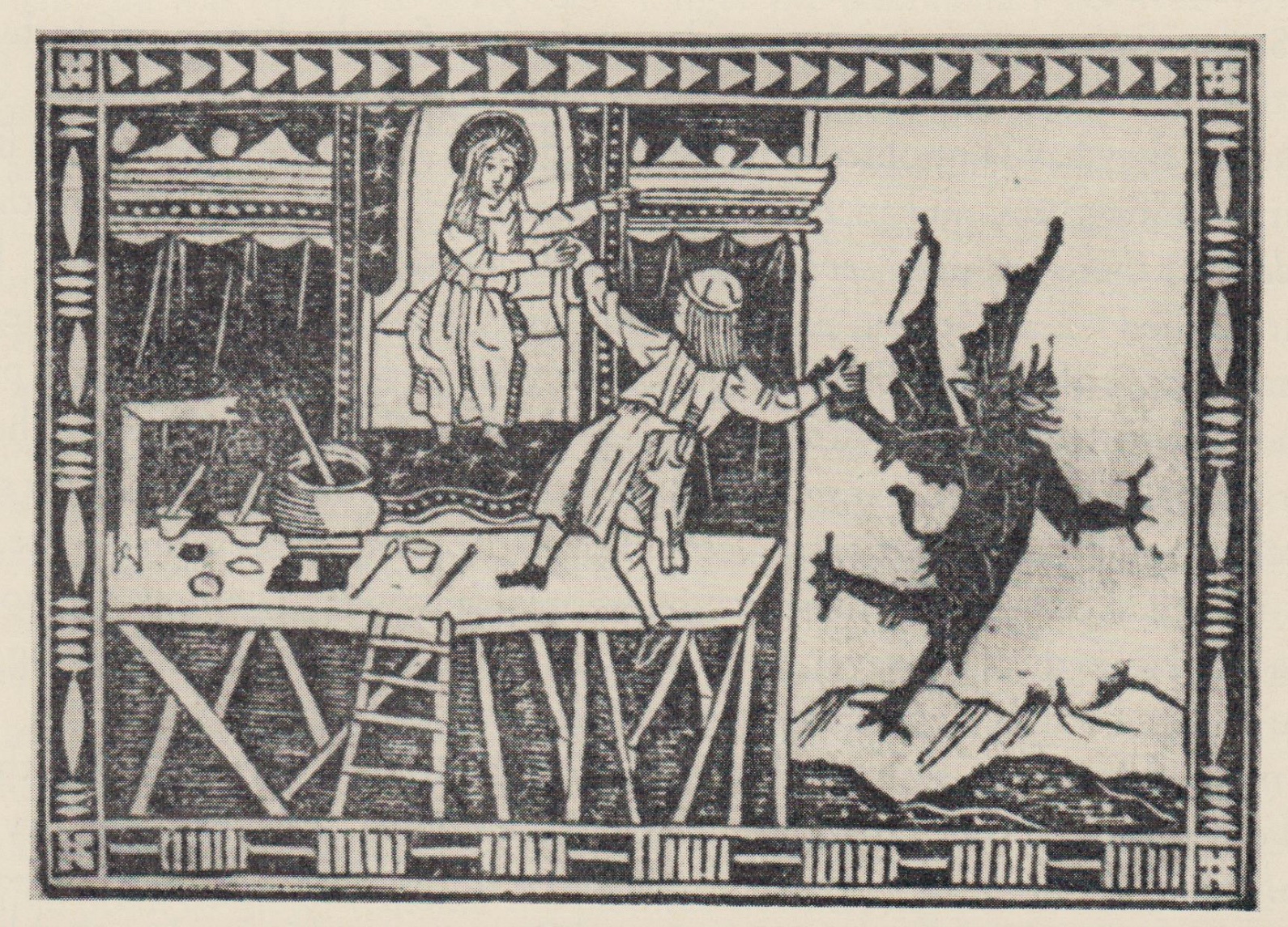

This picture shows a mural painter being saved from a fall by the Madonna they’ve just painted. I found this in a book on Renaissance painting in the Art School library years ago and it made a deep impression on me. This is a dramatic example – with the Devil holding one hand and the Virgin Mary the other – but basically I think it shows the struggle involved in making something. The pull between opposite forces can be thrilling and terrifying, and it could go either way. Somehow, I think these opposites need to be reconciled. There is something dangerous and precarious about the whole situation, especially if you’re on scaffolding.

When I look at the figure in the middle, I see Alasdair. In my view, the characters in Alasdair’s work – from Bella Baxter to Beatrice, for example – saved him from falls countless times. Alasdair was committed to his work and had a long and productive life because he got on with it, and he did so with love and sincerity. I can only admire this, and try to do the same.

To summarise Alasdair’s work in a few words, I would say, he told stories. And he tried to tell them as convincingly as possible. As we drew and painted more together, many things became clearer to me. One is that Alasdair worked in the Florentine style. In other words: strong outlines.

This picture shows a mural painter being saved from a fall by the Madonna they’ve just painted. I found this in a book on Renaissance painting in the Art School library years ago and it made a deep impression on me. This is a dramatic example – with the Devil holding one hand and the Virgin Mary the other – but basically I think it shows the struggle involved in making something. The pull between opposite forces can be thrilling and terrifying, and it could go either way. Somehow, I think these opposites need to be reconciled. There is something dangerous and precarious about the whole situation, especially if you’re on scaffolding.

When I look at the figure in the middle, I see Alasdair. In my view, the characters in Alasdair’s work – from Bella Baxter to Beatrice, for example – saved him from falls countless times. Alasdair was committed to his work and had a long and productive life because he got on with it, and he did so with love and sincerity. I can only admire this, and try to do the same.

To summarise Alasdair’s work in a few words, I would say, he told stories. And he tried to tell them as convincingly as possible. As we drew and painted more together, many things became clearer to me. One is that Alasdair worked in the Florentine style. In other words: strong outlines.

For several years I have been working with metal, including some attempts at engraving. I find it satisfying and difficult. Like most things, to reach a level of skill and precision will take time and practice. It is also a physical process, which can leave you with sore hands and stiff shoulders. I think physical exertion is something that particularly appealed to Alasdair about painting murals. There’s something about climbing scaffolding, craning your neck and holding tins of paint all day that leaves you with a very different kind of tiredness to what you’d feel from, say, writing.

Engraving basically involves using a tiny chisel, or a graver, to dig channels into metal. According to William Blake, “The greatest force flows through the most definite channels.”

This is one of Blake’s visions of the Last Judgement. I went to see this picture with Alasdair one day. It’s in storage, but it used to be in Pollok House, where it was displayed next to a sunny window for years so it’s badly faded. It’s watercolour and ink over pencil, but even with this delicate and faded picture I think it’s clear to see how important outline was to Blake. Michelangelo was Blake’s great hero and Blake was Alasdair’s favourite artist. Blake was an engraver by trade and I think it shows in everything he did. Blake says, “The great and golden rule of art, as well as of life, is this: that the more distinct, sharp and wiry the bounding line, the more perfect the work of art.”

If I had to describe Alasdair’s style – of his pictures and his writing – I would say it is an attempt at clarity. According to Blake, “Nature has no outline, but imagination has.” Alasdair’s imagination involved complex ideas and fantastic images, and he tried to express them and communicate them as best he could, and as clearly as possible. This approach has helped me a lot in life and I thank him for that.

I remember clearly the first drawing I worked on with Alasdair, for the Hillhead Subway mural: it was of the handsome old garage on Vinnicombe Street, which I believe is now a Nando’s. I think I did quite well to get my head round the strange geometry and forced perspective Alasdair was describing, and he seemed quite satisfied with what I’d drawn. But I know that my lines were tentative and lacking conviction. It made sense to me, and helped, when he said he wanted it to look more like a woodcut.

All of the drawings I worked on with Alasdair were done with pen. We didn’t use pencil much, sometimes just a few initial marks that would soon be rubbed out. And then you commit. Often Alasdair would do a sketch and I would turn it into an ink drawing, and the next day I’d come back and see that it had completely changed, that he’d added his distinctive tapering lines, cross-hatching and so on. It was a process of continual revision and improvement. When we started again or painted over something I quickly learned not to take it personally: it was just part of the process. It usually had to be done wrong first, before it could be done right.

There’s a passage in Lanark where he’s working on his tree of life mural and says of the tree, “It’s big and beautiful and in the wrong place. Far too central. It must be shifted two and a quarter inches to the left, fruit, birds, squirrels and all. Do you see why?” After spending every day with him for a few years I saw why.

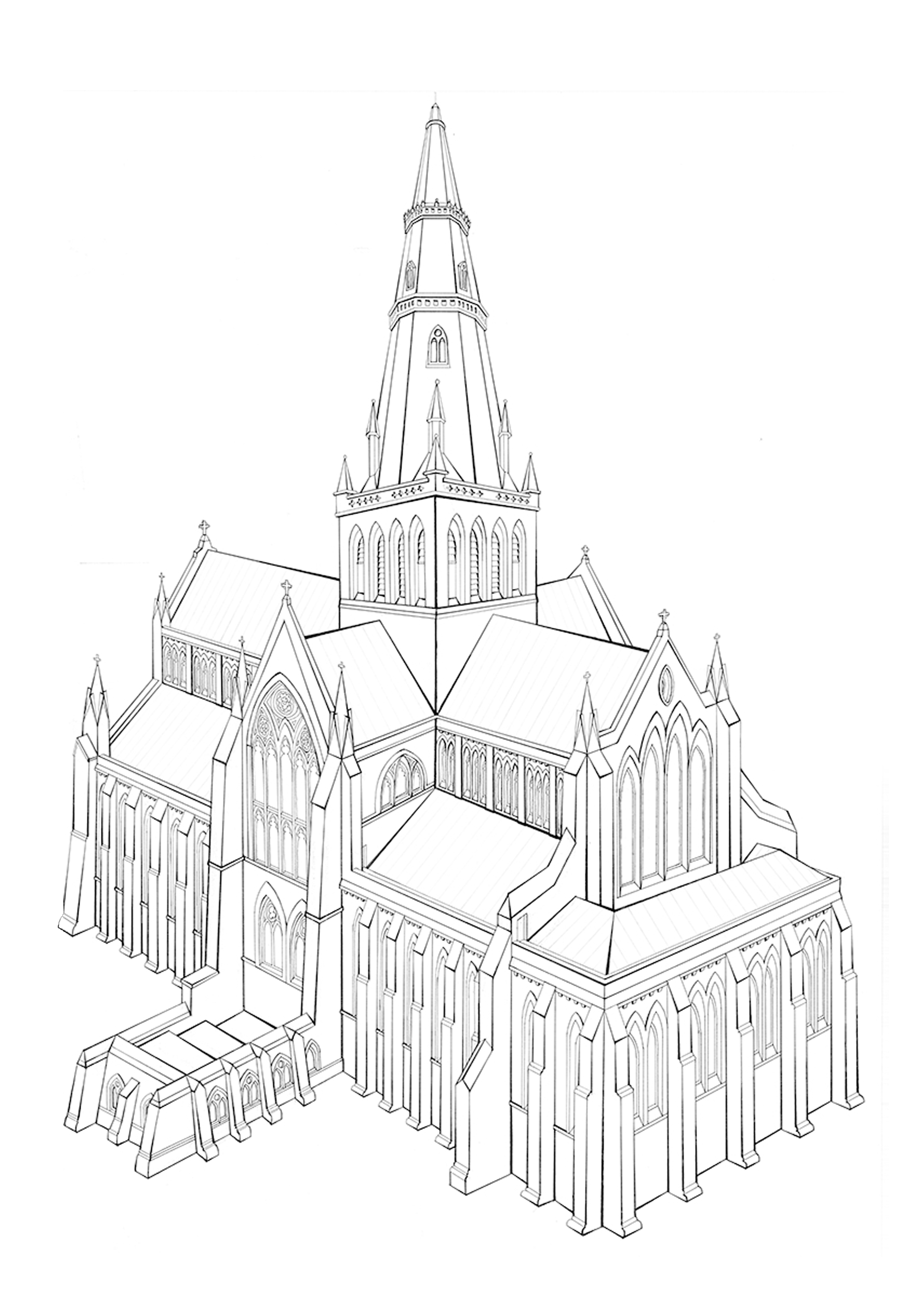

This is St. Mungo’s Cathedral, viewed looking down from the Necropolis, but with a sense of looking up at the spire. Alasdair sketched it out and told me everything he wanted it to show and I tried to fit it all in. Then he told me how thick he wanted the lines to be and I got on with it. Alasdair could see how he wanted to finish all of his pictures, but I knew there wouldn’t be time.

I remember the day Alasdair started translating Dante, which for the next few years brought him a lot of pleasure and comfort. He was amazed at Dante’s intelligence. Alasdair read his first few lines to me, and said he might carry on. I was pleased for him that he was able to finish.

It was already obvious to me on that day that he would be working on illustrations for the Comedy when he died. (That’s also what William Blake was working on when he died.)

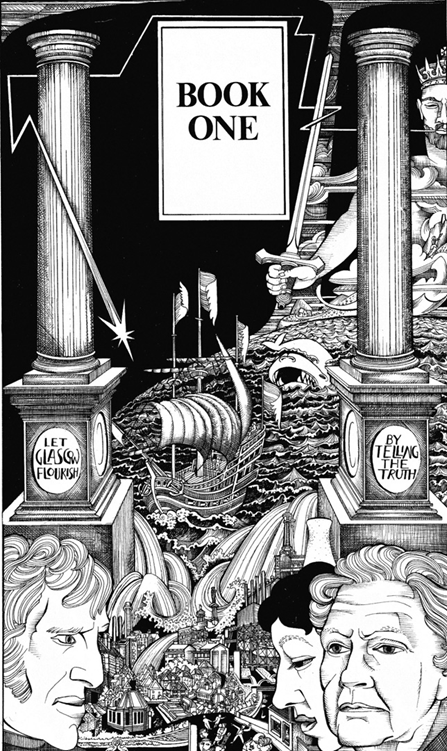

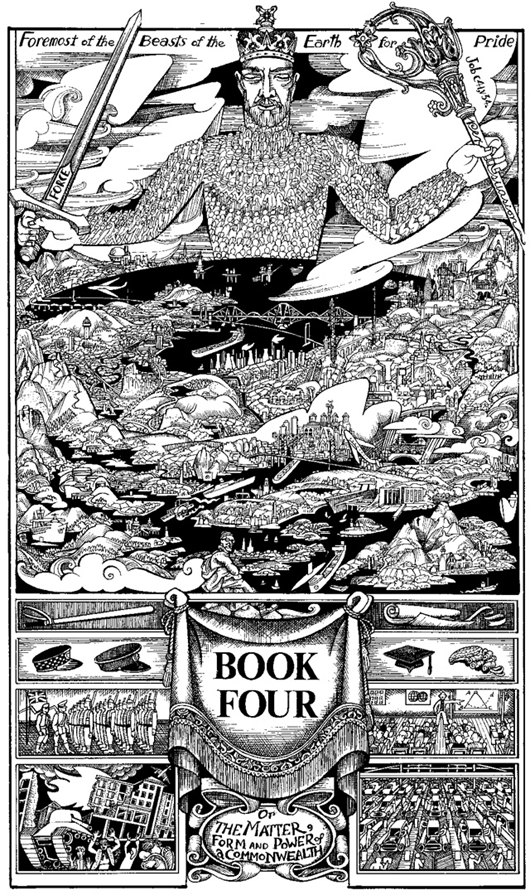

Alasdair was very good at stealing. Most of Lanark is taken from somewhere else. This is the Book One title page, adapted from that of Francis Bacon’s Novum Organum. At the base of the columns, which aren’t holding anything up, it says: ‘Let Glasgow Flourish, By Telling The Truth.’ This motto seems to have been around for centuries in various forms, from ‘Lord Let Glasgow Flourish by the Preaching of the Word’, to the shortened version in the 19th Century, ‘Let Glasgow Flourish’. I’m a lot less interested in ‘Let Glasgow Flourish’ without the second part of the sentence. I can see the appeal – for councillors and for the sake of tourism – of these branding campaigns like ‘Glasgow’s Miles Better’ and ‘People Make Glasgow’, but I don’t like them. Positivity, confidence and humour are all good and important traits, but I don’t think they’re anything to shout about. I worry that the bigger the billboards get, the less they reflect reality. And before you know it you’ve got some of the ugliest public murals imaginable, and way-too-many with Billy Connelly’s face on, all over the place.

To me it doesn’t look like Glasgow is flourishing. The old problems of poverty, violence, drunkenness don’t seem to be going away. Wherever I look I see buildings falling apart, the Winter Gardens left to ruin, the School of Art destroyed… Sauchiehall Street has a post-apocalyptic feel to it. And we’re told that People Make Glasgow, which I think is a meaningless combination of words. But I like this one with the Telling the Truth bit, because it suggests that there’s work to do. I think it speaks to a kind of responsibility or civic duty that we all have.

I was asked to make something to mark the 40th anniversary of the publication of Lanark. I made a pair of silver signet rings and engraved these words. If nothing else, when I put them on I’m reminded to tell the truth. It seems to me that the most important truth we need to face is, We’re Fucked. If we continue to ignore this truth, I don’t suppose our species will survive for much longer. Things need to change quickly and radically, starting with… people telling the truth, being nice to each other, showing some respect for Mother Earth etc. It might already be too late, but it’s worth a shot.

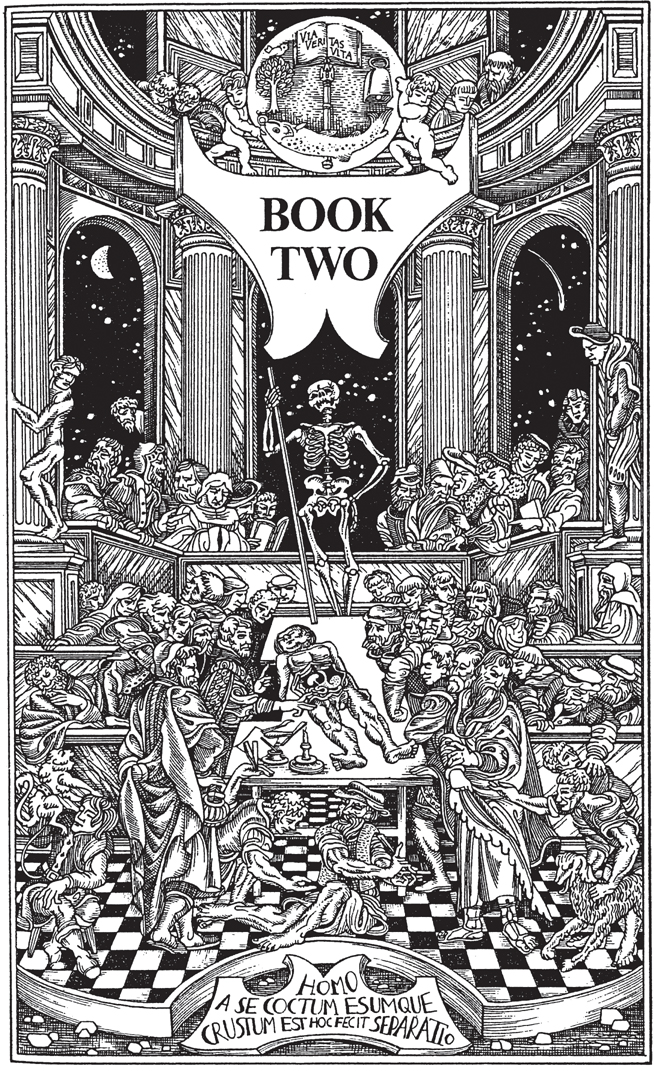

The title page of Book Three is from Walter Raleigh’s History of the World. There’s plenty more Latin here, which I like to use because it sounds nice. But I find the skeleton at the bottom even more appealing. Mors Oblivio 1614 – 1979.

I made a ring with a skull on it, and tried to simplify the drawing as much as possible with a single outline. At first I did this as an engraving but it wasn’t a very convincing skull and I wanted the image to be stronger, so I used another piece of silver, cut the lines with a saw, and soldered it on top. The uneven pattern and colour is fire scale and flux from soldering, which usually you’d get rid of and clean up, but here I decided to keep.

I wanted the last piece to be as simple and clear as possible. I think the sooner Scotland becomes independent the better. Then the hard work really starts.